Common Mistakes to Avoid When Applying Conformal Coating

- Electronic Potting Material Manufacturer

- February 13, 2026

- Acrylic Conformal Coating, acrylic vs silicone conformal coating, circuit board potting compound china wholesale, circuit board potting compounds, conformal coating, conformal coating electronics, conformal coating for electronics, conformal coating for pcb, conformal coating for pcb standards, Conformal Coating in Electronic, conformal coating in electronics market, conformal coating manufacturers, conformal coating market, conformal coating material, Conformal Coating Material Manufacturer, Conformal Coating Material Supplier, conformal coating material types, conformal coating overspray, conformal coating pcb, conformal coating process, conformal coating silicone, conformal coating spray, Connector Potting Compound, deepmaterial potting compound, deepmaterial potting compound manufacturer, electric motor potting compound, electrical potting compound, electronic epoxy encapsulant potting compounds, epoxy potting compound, polyurethane potting compound, polyurethane potting compound for electronics, potting compound, potting compound for electronics, potting compound for pcb, potting compound vs epoxy, potting material for electronics, potting pcb, silicone potting compound for electronics, uv conformal coating manufacturer, UV curing potting compound, waterproof potting compound

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Applying Conformal Coating

In the world of electronics manufacturing, the difference between a product that lasts a decade and one that fails in the field often comes down to a layer of material less than a millimeter thick. Conformal coating is the armor that protects printed circuit board assemblies (PCBAs) from the ravages of moisture, dust, chemicals, and vibration. When applied correctly, it ensures long-term reliability in even the harshest environments.

However, the application process is fraught with pitfalls. Because the coating is transparent and the defects are often microscopic, mistakes can easily go unnoticed until a unit fails in the field. To achieve a robust, high-yield coating process, one must understand not just what to do, but what not to do. Here are the most common mistakes engineers and technicians make when applying conformal coating and how to avoid them.

Inadequate Surface Preparation

The single most common cause of coating failure is poor adhesion. Conformal coating will only protect a board if it sticks to it. If the surface is contaminated, the coating can delaminate, allowing moisture and contaminants to creep underneath and wreak havoc.

The Mistake: Rushing or skipping the cleaning process. This includes failing to remove flux residues, fingerprints, mold-release agents, and dust. Many manufacturers assume that a board fresh from the assembly line is “clean enough,” but ionic residues from wave soldering or reflow are highly conductive and hygroscopic (moisture-attracting).

The Consequence: If the board is contaminated, the coating may bubble, peel, or lift away from the surface over time. Capillary action can then draw corrosive materials under the coating, leading to electrochemical migration and dendrite growth, which cause short circuits.

The Solution: Implement a rigorous cleaning verification process. Use an ionic contamination tester to ensure boards meet cleanliness standards (e.g., < 1.56 µg/cm² NaCl equivalent). Immediately prior to coating, a final cleaning step using a suitable solvent (like isopropyl alcohol) or a plasma treatment process should be used to remove any handling residues. The board must also be completely dry before coating begins.

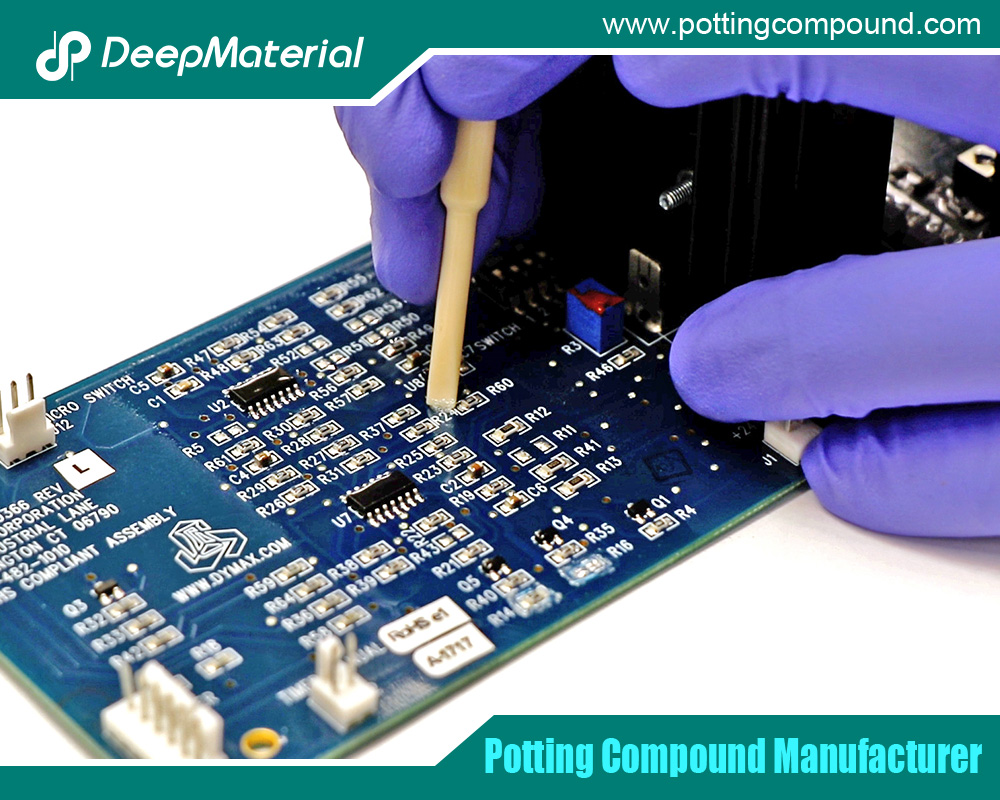

Neglecting the Masking Process

Conformal coating is designed to protect circuits, but it is an insulator. If it gets where it shouldn’t be, it acts as a contaminant.

The Mistake: Failing to mask, or poorly masking, areas that must remain uncoated. This includes connectors, test points, battery contacts, heat sinks, high-voltage areas (where coating can crack due to arcing), and components that are sensitive to solvents, such as some electrolytic capacitors, potentiometers, and trimmers.

The Consequence: Coating on connector pins can create an insulating barrier, causing intermittent connections or complete failure when the mating connector is inserted. Coating inside a relay or switch contact can prevent the device from functioning entirely. Furthermore, cleaning overspray from these areas is time-consuming, expensive, and risks damaging the board.

The Solution: Develop a detailed masking diagram for every board type. Use high-temperature silicone rubber boots for repeatable, reusable masking of connectors. For odd-shaped components or one-off jobs, use high-quality polyester or polyimide (Kapton) tapes. Ensure the tape is burnished down tightly to prevent “leakers” (capillary action drawing coating under the tape edge). For high-volume production, consider investing in automated selective coating robots that eliminate the need for masking altogether by applying coating only where it is needed.

Selecting the Wrong Material

Conformal coatings are not one-size-fits-all. There are five main chemistries: Acrylic (AR), Urethane (UR), Epoxy (ER), Silicone (SR), and Parylene (XY). Each has distinct mechanical and chemical properties.

The Mistake: Choosing a coating based on cost or availability alone, without considering the product’s operational environment. For example, using an acrylic (which offers good moisture resistance but poor solvent resistance) on a board that will be regularly cleaned with aggressive solvents.

The Consequence: The coating may dissolve, swell, or soften upon exposure to the environment, losing its protective properties. Conversely, using a hard, brittle epoxy on a flexible circuit or in a high-vibration environment will result in cracking.

The Solution: Match the chemistry to the application.

-

Acrylics (AR): Easy to apply and remove (for rework), good moisture resistance, but poor solvent/abrasion resistance. Good for general-purpose consumer goods.

-

Urethanes (UR): Very good abrasion and solvent resistance, but difficult to remove. Ideal for automotive and industrial controls.

-

Silicones (SR): Excellent for high-temperature and high-flexibility applications. Superior dielectric properties but soft and easily damaged. Perfect for power supplies and LED lighting.

-

Epoxies (ER): Excellent hardness and chemical resistance, but high stress on components and nearly impossible to rework. Best for harsh industrial sensors.

-

Parylene (XY): Applied via vacuum deposition, offering pinhole-free coverage with the lowest dielectric stress. Ideal for medical implants and MEMS devices, but expensive and requires specialized equipment.

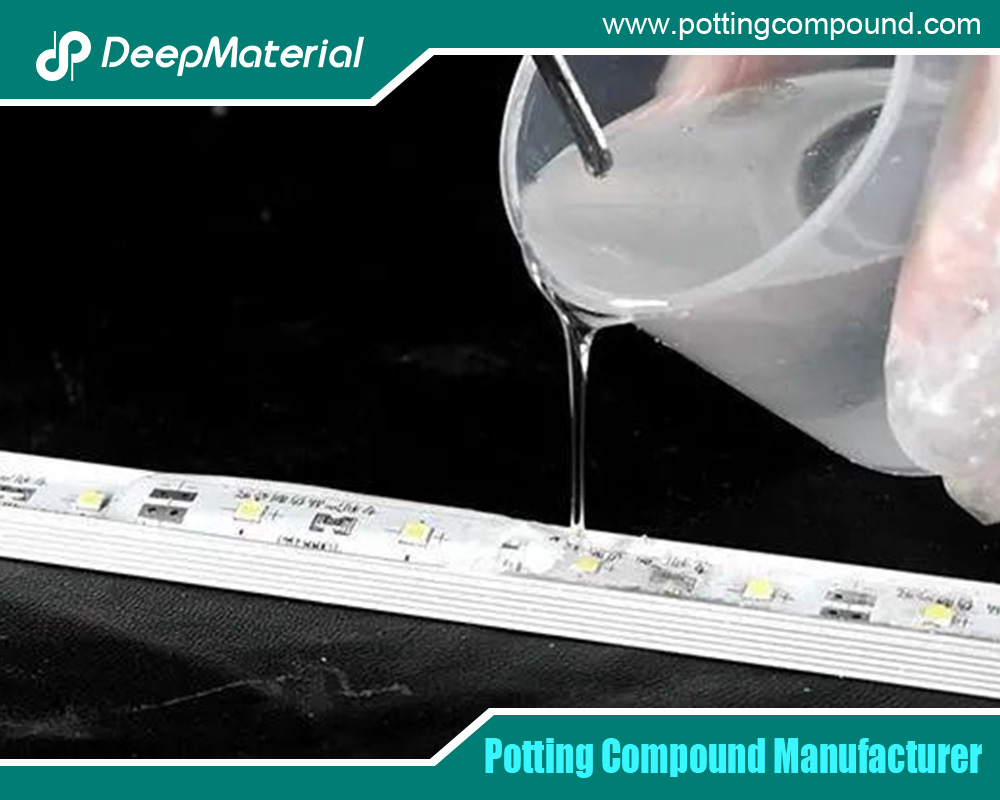

Applying the Coating Too Thickly

The word “conformal” means the coating should follow the contours of the components. It is not meant to be a thick, globbed-on layer of plastic.

The Mistake: Applying a coating that is too thick, either by passing too slowly with a spray nozzle, using too high a viscosity, or applying multiple coats without proper drying. Operators often mistakenly believe that “more is better.”

The Consequence: Thick coatings can crack due to thermal expansion and contraction. They can also place undue mechanical stress on delicate component leads and solder joints. Furthermore, thick layers take much longer to cure and can trap solvents, leading to outgassing and bubbles later in the product’s life. Excess material in tight spaces can also act as a thermal insulator, trapping heat and shortening component lifespan.

The Solution: Adhere strictly to the manufacturer’s specified thickness, usually measured in microns (typically 25–75 µm for most coatings, 50–200 µm for silicones). Use a wet film thickness gauge during application or measure cured samples using an eddy current probe or micrometer. If using spray application, ensure proper atomization and a consistent pass speed.

Ignoring Compatibility and Cure Profiles

The relationship between the coating, the flux residues, and the components themselves is a delicate chemical dance.

The Mistake: Assuming all materials on the board are compatible with the coating solvent and curing temperature. For instance, applying a solvent-based coating onto a “non-sealed” component like a trim potentiometer, relay, or socket.

The Consequence: The solvents in the coating can wick into the component housing, dissolving lubricants or attacking the internal plastic housing. This leads to “solvent entrapment,” where the component fails internally weeks or months later. During curing, if the temperature ramp rate is too fast, the board can suffer thermal shock, cracking ceramic capacitors.

The Solution: Consult the coating manufacturer’s compatibility charts. For sensitive components, ensure they are either masked or specified as “sealed” or “washable.” When curing, follow the recommended thermal profile. If the coating requires high heat, use a gradual ramp rate (e.g., 1–2°C per minute) to allow the board and components to expand evenly.

Inadequate Inspection and Quality Control

Because conformal coating is transparent, defects are often invisible to the naked eye under standard lighting.

The Mistake: Relying solely on a quick visual glance under a desk lamp to verify coating quality. Operators miss thin spots, “fisheyes” (contamination), or incomplete coverage on the underside of components.

The Consequence: Voids or thin areas become pathways for corrosion. A pinhole over a fine-pitch IC lead can allow moisture to reach the bare metal, leading to dendritic growth and a short circuit that only appears after months of use.

The Solution: Implement a multi-stage inspection protocol.

-

In-Process: Inspect the board immediately after coating under UV light if a UV-traceable coating is used.

-

Optical: Use a stereomicroscope with adjustable lighting to examine high-risk areas (e.g., under chip components).

-

Automated Optical Inspection (AOI): For high-volume lines, invest in a conformal coating AOI system that uses laser triangulation and UV cameras to map thickness and coverage automatically.

Underestimating Curing and Handling

The moment between application and final cure is the most vulnerable time for a coated assembly.

The Mistake: Handling boards before they are fully cured or placing them in an environment with airborne contaminants during the curing process. Another common error is using the wrong curing method—for example, relying on air-dry for a material that requires heat to achieve full chemical resistance.

The Consequence: Touching a wet board leaves fingerprints in the coating. Dust settling on a wet board becomes embedded in the protective layer, potentially creating a wicking path for moisture. If the board is not fully cured, the coating will remain tacky or soft, failing to provide adequate protection.

The Solution: Create a designated clean area for curing, free from dust and drafts. Understand the difference between “dry-to-touch” and “fully cured.” Follow the manufacturer’s time and temperature guidelines exactly. If using UV-cure materials, ensure the UV light intensity is measured regularly, as bulbs degrade over time.

Forgetting About Rework and Repair

Even with the best processes, boards sometimes fail. When they do, the conformal coating becomes a barrier to repair.

The Mistake: Selecting a coating without a plan for how to remove it. Technicians often resort to brute force—scraping with a knife—which damages the board, lifts traces, and destroys solder masks.

The Consequence: Repairable boards become scrap. Field service costs skyrocket as technicians struggle to perform simple component replacements.

The Solution: Design for reworkability. If the product is likely to require updates or repairs, choose an acrylic coating, which can be dissolved with solvents like isopropyl alcohol or specialized strippers. For urethanes or epoxies, train technicians on the use of selective soldering tools or micro-abrasive blasting systems (using a medium like sodium bicarbonate) to remove the coating without damaging the underlying circuitry. Always have the appropriate chemical stripper validated and available in the repair kit.

Conclusion

Applying conformal coating is a critical process that sits at the intersection of chemistry, mechanics, and electrical engineering. By avoiding these common mistakes—rushing preparation, ignoring masking, selecting the wrong material, applying it too thickly, overlooking compatibility, and failing to inspect—manufacturers can dramatically improve the reliability of their electronic assemblies.

A successful coating strategy requires a holistic approach: clean the board meticulously, choose the right weapon, apply it with precision, and verify the results. When done correctly, this invisible layer provides an impenetrable shield, ensuring that the electronics inside a car, a pacemaker, or a satellite survive to perform their duty for years to come.

For more about common mistakes to avoid when applying conformal coating, you can pay a visit to DeepMaterial at https://www.pottingcompound.com/ for more info.

Recent Posts

- Conformal Coating vs. Potting: What’s the Difference for Your PCB?

- Common Mistakes to Avoid When Applying Conformal Coating

- How Does Potting and Encapsulation Protect Electronic Components?

- How to Prevent Voids in Circuit Board Potting: A Comprehensive Guide to Reliable Encapsulation

- How to Choose the Right Potting Material for Your PCB

- Basic Knowledge, Methods and Materials about Electronic Encapsulation

- Electronic Encapsulation Technology to Enhance the Durability of Automotive Electronics

- The Unsung Guardian: Why Silicone Potting Compound is Widely Used in the Electronics Industry

- The Development Trend and Future Prospects of Electrical Potting Compound in the Glue Industry

- The Conformal Coating for PCB Market Has Entered an Explosive Period: Key Drivers and Reports Detailed

Tags

Related Posts

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Applying Conformal Coating

How Does Potting and Encapsulation Protect Electronic Components?

How to Choose the Right Potting Material for Your PCB